The Hmong people fought alongside American soldiers against Communist forces during the Vietnam War. When the U.S. pulled out of the region, their Hmong allies were left to fend for themselves. Knowing that staying in Laos meant their deaths, many fled across the Mekong River into Thailand before immigrating to the U.S.

“I never dreamt that I would be here in the United States,” said Cheruchia Vang, a Hmong veteran. “It suddenly happened. United States pulls out its troops from Asia and then we have no choice. We never thought that we should be here and my children would not be born here.”

Vang served as a paymaster during the war, traveling to the front lines to pay soldiers. One of his worst memories, and a frequent nightmare, is the day he was captured by North Vietnamese forces. He was able to escape, but the experiences are always with him. Vang said he and other Laotian veterans deserve to be honored for their service during the war.

“We contributed. We sacrificed our life on behalf of the United States soldier,” Vang said. “So they should treat us the same way as they treat American soldier here.”

Vang is one of the thousands of Hmong veterans asking Congress to pass a bill introduced by Central Valley congressman Jim Costa.

The Hmong Veterans’ Service Recognition Act would give Hmong veterans the right to be buried in national cemeteries. Along with that benefit would come some assistance with burial costs and grave maintenance.

“The financial burden for anyone preparing for a funeral is a big deal,” said another Hmong veteran, Mao Vang, through an interpreter. (Vang is a common name in the Hmong community, but none of the Vangs in this story are related by blood.) “Those who are elder, it’s a big burden to them.”

Rep. Costa has introduced similar measures four other times, but this time the legislation has bipartisan support in both the House of Representatives and the Senate.

The Hmong veterans in Fresno say they lost their friends, family and homeland. Their numbers are dwindling as veterans die from old age and war wounds. Those who survive desperately want to be recognized for their service.

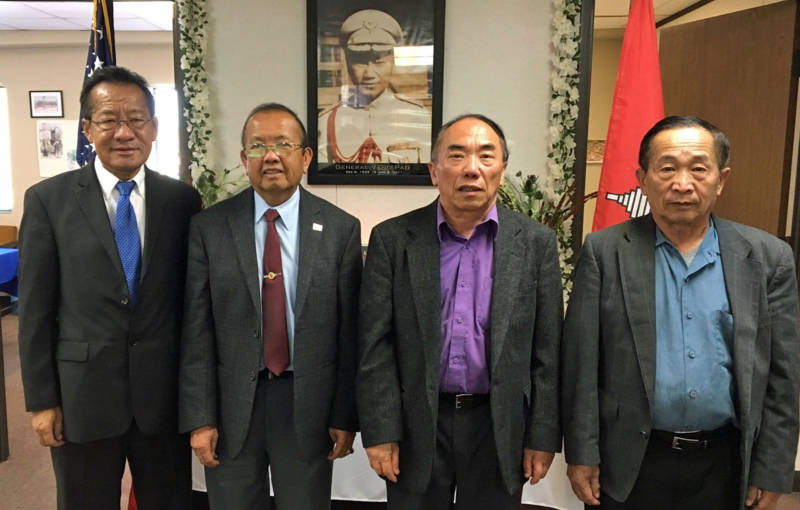

“You don’t know how hard it is,” said Peter Vang, executive director of Lao Veterans of America. “You came here. You don’t speak the language. You don’t know the culture. You suffer every day, not to mention all the war trauma you went through.”

Peter Vang is not a veteran himself, but he immigrated to the U.S. at 15 with his father, who was a veteran. At Lao Veterans of America, he advocates on behalf of veterans and helps connect them to services.

He still remembers life during the war, when he never knew if his father would walk in the door, alive and well, or if he’d come home in a body bag. Now his father is aging and doesn’t want to die before he knows he’ll be honored in the same way as his American brothers.

Read more at KQED News